ANONYMOUS IN CONVERSATION WITH TRAVIS WYCHE

Let’s begin with your description of the political situation in Myanmar and your role in that context. You are an American artist interfacing with an artist-organized, decentralized network in Myanmar with music serving as the driving force for generating and distributing value while also increasing cultural awareness and reciprocal connections between the two cultures. There’s something here that we might touch upon concerning resource management as well, although management might not be the best word in this context. Let’s start with you illustrating the situation as you see it, for an audience that might know very little about it.

In order to understand the current situation in Myanmar we must try to understand the history of the country. It was a British colony in the early 1900s and in 1946 a man named General Aung San led the People’s Army — what would later become the military of Myanmar — to push the British out so that Myanmar could be a self-actualized nation state of its own and no longer a colony of the English. He was elected to be their first Prime Minister and was assassinated within the first year of being elected by members of his own military. It was a coup. He had a daughter who became a widely recognized figure, named Aung San Suu Kyi, known as the mother of democracy in Myanmar. She has become very iconic. There was even a movie made about her in 2011 shortly after she was released from house arrest called The Lady that is quite good.

Aung San Suu Kyi went to England to attend university where she married a British man and bore children. In 1988, she returned to Myanmar to take care of her mother who had become hospitalized. While she was there, she witnessed a massacre of students and activists in front of the hospital. A crowd of innocent people was completely gunned down by tanks. She was approached by members of an activist group and they conveyed that she had become a figurehead of the revolution. She was compelled to stay, leaving behind her life in England to join the resistance formed around a revolutionary idea. This is 1988.

Long story short, the government in power tried to use psychological warfare to get Aung San Suu Kyi out of the country. They knew that they couldn’t just kill her because she was too visible in the global sphere of influence, so instead the military put her under house arrest and refused to let her husband and children come visit her anymore. They told her that they would fly her back to England, but once she left she wouldn’t be allowed to come back. Aung San Suu Kyi refused to go, so she lived in isolation for 15 years of her life. During that time her husband died of cancer and her children grew from teenagers to grown men. In 1991 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, but she was still under house arrest so her husband and children went to receive it for her.

Then we get to a period of time that’s closer to my experiences in Myanmar. I went to Thailand in late 2008 and met a Burmese performance artist in a punk band the first night I was in Chiang Mai. I also befriended a German filmmaker. I quickly became aware of the punk-anarchist-revolutionary spirit in the arts and music scene in Yangon, poised against the brutal government regime. It’s wasn’t the same as punk in the US, although there are certainly members of the American punk scene that — due to ethnic or cultural ties — might feel more aligned to what I’m going to say about people from Myanmar. There was a strong sense of aesthetics; Rebel Riot from Yangon was adorned in 70s style liberty spikes, like British Oi punk. These people grew up with Theravada Buddhism and have spoken at length about the right to self actualization as a central premise of their beliefs. In the scenario I’m presenting to you, we should remember that the oppressive force is motivated to deny any individual rights to self-actualize, suppressing people in both their physical and spiritual lives, in all the different dimensions that they exist.

This Myanmar punk band ran a Food Not Bombs in Yangon to feed people and organized squats and anarchist collectives, believing that as long as the military regime was in control of their country they could not self-actualize. Concurrent with these events, there was an underground network of performance artists and poets that began using a coded poetic language to subtly press against the edges of what is censored publicly on the streets of major cities like Yangon or Mandalay. One of the artists was a central figure named ____who organizes a festival called Beyond Pressure.

I went to Myanmar for the first time in 2009 with the German filmmaker I mentioned earlier. She was discovered with a video camera at the border and was asked to leave, meaning that she was not given an official deportation but was not allowed back into the country…

Was it common knowledge at this time that video cameras were banned? Was the government trying to suppress the production of documentation of what was happening there?

Yes. At the border between Myanmar and Thailand there’s a lot of young European and Australian people who will go and work at the refugee camps for a year between college, so people become very aware of what’s going on. There’s an influx of refugees trying to flee the country to come into Thailand, which is a poor country that can’t support a large number of refugees, so they end up staying in these camps for what is sometimes a significant part of their lives because it’s better than going back to Myanmar. Through the networks of people fleeing systemic oppression and congregating at the borders, journalists and artists were able to smuggle video cameras to the front lines. There was a whole network of filmmakers who were squeezing out footage of the intense violence to a place called the Yangon Film School in Berlin where students began piecing together documentaries from the smuggled footage. This was before cell phones became super sophisticated, pre-2010. Now the ubiquity of mobile devices makes it easier to resist some of these oppressive attempts.

You’re reminding me of a pivotal concept identified by Michel Foucault and other theorists, like Brian Holmes, regarding the shift from a surveillance state based on the centralized panoptic control of media outlets to a sousveillance scenario where all of the citizens are documenting themselves and each other. With the decentralization of perspective comes a radical shift in power as the POV of people on the ground becomes exceedingly more difficult to regulate and censor. This might empower individuals that are trying to push information through a fire-walled data sieve or media blockade of censorship.

By the time I arrived in 2009, one topic that was always discussed within Burmese artist circles was the difficulty of trusting anyone. If you did trust somebody, you trusted them with your life. As a result, a highly codified poetic language began to form where all reference was obscured by allusion while the people continued to conduct discussions or plot strategies. If these conversations were overheard outsiders would have no fucking clue what the content was. They might become suspicious, but nothing could be proven.

I hear you describing a method of encryption, poetic cryptography, a codified use of language. Poetic language is known for its allegorical, fluid character, but I’ve never considered the potential implementation of poetics as a form of encryption so literally.

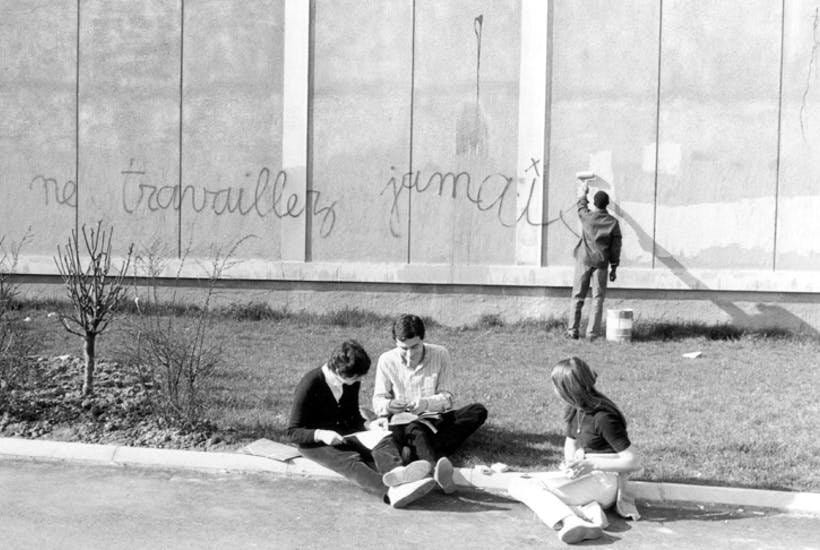

What we’ve witnessed in America recently with right wing factions co-opting the language of Black Lives Matter and minority struggle, co-opting the tools of resistance, is a struggle between explicit resistance and plainclothes surveillance. It really comes down to saving one’s own ass for a lot of people, because if you get busted the government could threaten your family or imprison, torture, or just quietly extinguish you. So they choose to play a part in the sousvelliance. The use of technology is going in two different directions: plainclothes people sousveying anything that could potentially be considered politically provocative through their personal mobile devices, and this other group of people smuggling video out of the country to create documentaries shown beyond the borders. **_ organized these performance art events — Beyond Pressure — that were out in public, in the open for everyone to witness. The highly poetic nature was pushing against the acceptable limits imposed by the oppressive regime.

The performance of various roles determines the accessibility — the constraints — that are imposed upon the individual. You’re calling our attention to the explicit visibility of being able to identify individuals through surveillance and sousvelliance, yet there’s also a much more nuanced orchestration of aesthetics here. For example, the Neo-conservative American Right produce Make America Great Again hats associated with Trump supporters, but largely the right is identified by the normalcy — or invisibility — of their aesthetics. They are difficult or impossible to distinguish. Anonymity is the strength; strength in numbers. Hoards of stampeding white men that blur together with the American flags they wave in their Nationalistic fervor as they rush the Capital Building like marauding barbarians.

This constitutes a wielding of anonymity as a weapon against the woke, against the Neo-liberal left. We have witnessed similar things in youth culture. The culture of punk, hardcore, or similar underground music cultures once felt incredibly authentic, but eventually even the most radical peacocking was appropriated back into the capitalist, consumerist, materialist mainstream as fashion rendered inert, rendered opaque, ripped from its antagonist origins to be neutralized, cauterized, made impotent as a fashion statement.

You and I witnessed this in returning to Oakland after several years of being away. The intentionally standardized mode of black t-shirt and black pants that used to connote a sense of camaraderie with the black community and the local anarchist idealism of punk culture — and also as a way of sloughing off the abhorrent rainbow-pop consumerism sprouting up all around us — had become associated with tech culture, associated with wealth and gentrification, with a group of people seemingly devoid of values.

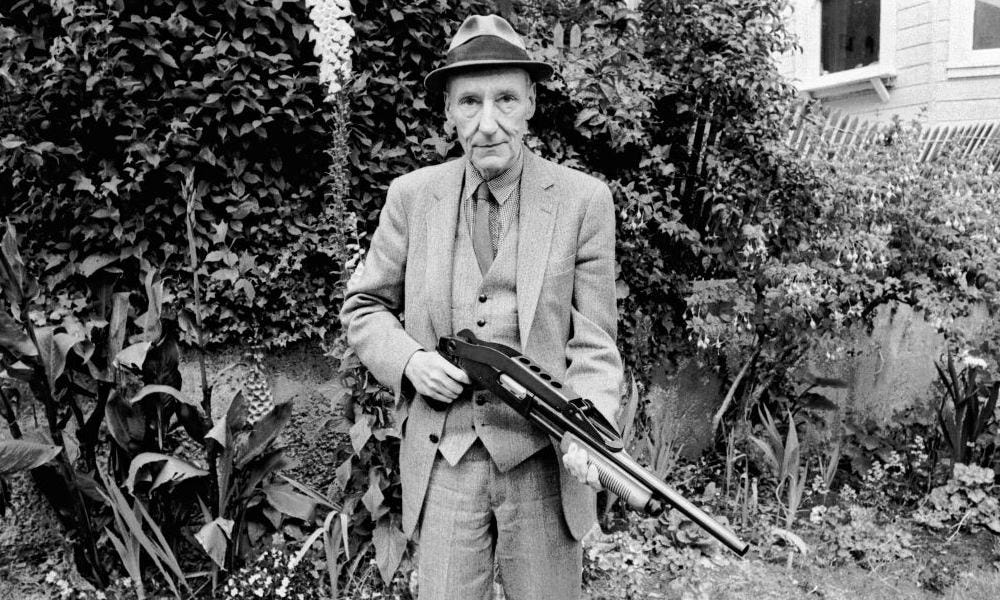

The shifting of those associations is fascinating. Some groups utilize extreme aesthetic sensibilities, such as these Oi-Buddhist punks of Myanmar, and others strive to melt into the general population, to become anonymous, even radically anonymous, in order to wield their anonymity as a political tool. Another association: I read an interview with William Burroughs many years ago and the interviewer asked him why he always wore the same gray suit in every picture that he had ever appeared in. Burroughs dressed like a 1950s business man, but of course he has come to be recognized as one of the most radical cultural icons for a psychedelic Beat youth subculture of literature, poetry, gay identity, insane drugs, potent sci-fi, and all the rest. How could he dress so conservatively? William Burroughs’ response was (and I’m paraphrasing): look at the fucking hippies and look at the attention that they’re getting. They make themselves targets for the police. They’re the first ones that get thrown in the back of the paddy wagon. They’re rejected by all of culture, by both sides, by their parents, by their peers, and by the society at large. They are self-oppressed because they have rendered themselves impotent. So I wear the uniform of the ruling class so that I can blend in and get the important information across enemy lines, and believe me the enemy is always watching.

In 2012, *_ — who organized the Beyond Pressure festivals — received a grant from a foundation that funds artists who are pushing against fascist regimes. _* received this grant and then brought some Burmese artists out of Myanmar, which is not a very easy thing to do even in 2012. In 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest after 15 years of being imprisoned in her own home while Myanmar is celebrating a move towards democracy, although no one really yet knew what that would mean. **’s first question was how easy will it be for Burmese artists to leave Myanmar and he was able to get five of them into Malaysia. We did some performance art workshops in Kuala Lumpur and then traveled to Myanmar to test the boundaries of what we could get away with. Would the government even issue us visas to come into the country?

In Mandalay, we witnessed a very large protest because the ‘government’ systematically shuts off the electricity for periods of time. Nobody knew how long it was going to be off or when these intentional blackouts would happen. In a tropical climate, this is a terrible thing for many different reasons, with food preservation being one of the most important. So there’s a massive protest in front of the palace with people lighting candles to protest the shutting off of the electricity.

Was there an explicit purpose for shutting off electricity? Was it to control communications and to take down channels of communication? To exert brute force control over the people to remind them that they are being dominated?

I would say all of the above. As long as most of my Burmese friends can remember, the electricity has been periodically shut off during times of unrest as a form of psychological warfare. The food spoils quickly and this is a place where many people are going hungry already. Then there is the constant discomfort of not having a fan in 99F weather, which can be especially brutal if you don’t know when it’s going to stop. And of course, communications are disabled in those periods of time. This is just one example from a series of tactics used to oppress the people. Another is when the government decided to change the money. ** was a teenager when it happened so he remembers it well enough to compose a performance art piece about it.

The government discontinued the use of one currency and replaced it with another to render everything in circulation obsolete?

Yes, and it happened overnight. Many Burmese people only use cash and don’t have bank accounts, so literally overnight their accumulated wealth became utterly useless and they were denied access to trade markets to exchange for the new currency. The people just woke up one day to discover that they had absolutely nothing.

With this shift in currency and the total breakdown of economic and communicative accessibility, the tyrannical government was just wringing the life out of these people. I want to go as deep into the weeds as you’re willing to lead me to learn why this is happening and how the government was rationalizing the situation to the rest of the world. I’m embarrassed to admit how naive I am about this entire situation and I hope you can help me find resources so I can get up to speed on these events. I’m horrified that people around me are not talking about this more openly.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratic party were finally voted into power in 2015, but it was kind of a puppet show since the military was still guaranteed 25% of the Parliament seats. The system that had been responsible for the oppression of the entire country from 1947 until this minute have never been put on trial. When the People’s Revolution happened in El Salvador the military and government members were put on trial for the massacres, tried and put into prison. The system of oppression in Myanmar has been passed down through multiple generations, yet there’s no clearly identifiable figurehead. We witness the stalemates that take place here in the US, but if you’re sharing a parliament with people who have allowed massacres to take place there is an entirely different system of coercion, corruption, and fear underway. In February of this year the recent election in Myanmar was deemed a fraud even though there was no evidence to support this claim. The military just put everybody in prison with no due process. There are allegations that Aung San Suu Kyi is guilty of owning illegal walkie talkies and inciting fear around COVID, which somehow justifies her being kept in the highest security prison in Myanmar, the same prison that ** was recently released from.

What I would really like to hear about is the grassroots, decentralized, subcultural movement that’s active on the ground, coordinated by your artist community. What kinds of strategies are being implemented to circumnavigate centralized control? What has been attempted and failed, or what is currently underway with this international collaboration effort? Earlier you mentioned that trust and social credibility are so essential and at this point perhaps even more valuable than currency. How is social credibility built? How is it formed? How is it imagined? How is it distributed? How does this network of people that have had everything taken away from them successfully mobilize against the panoptic surveillance government leveraging brute military strength, in control of all the means of production and all of the resources?

It has been almost a decade of slowly pushing towards freedom, although there is still a lot of censorship. Strategic oppression continues with the Rohingya people on the western border with Bangladesh and the hill tribe people on the eastern border, but this certainly extends beyond the scope of our time today. However, people in the center of Myanmar and people in cities like Yangon are experiencing the closest thing to freedom that they’ve had. They are benefiting from the global exchange of artistic ideas, through entrepreneurship, education, music, art, and all the rest. The doors for tourism into Myanmar are much wider than they have ever been before.

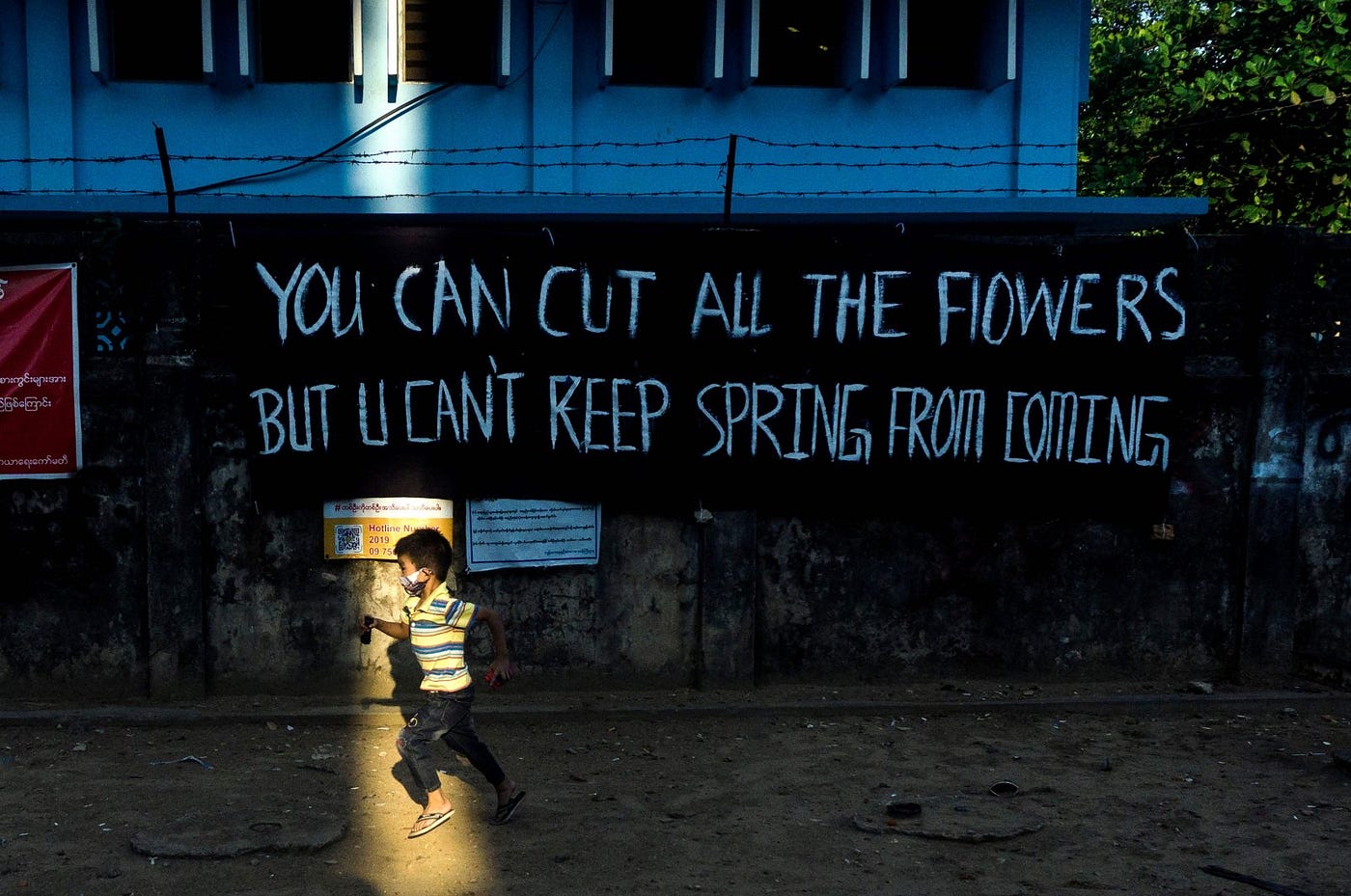

There’s a younger generation that is not afraid to put their foot down, so the streets exploded in February. Everyone was posting videos on social media of the massive protests in the street and it was relatively jovial. There were hilarious and cute artistic interventions, well rendered artful images of protest, and it did not seem particularly violent. There was police presence on the streets, but you didn’t hear too much about people being killed. As the protest got bigger due to their voices not being heard, the violence on the street grew proportionally and the reports accounted an increased daily death count.

Now there are resistance fighters, a people’s army out in the jungle training. The nationwide resistance is supported by the communal sharing of resources. Even though nobody really has much, they are willing to share with everybody around them. One of my friends is very concerned because her family had not been making any money. They organize soup kitchens where all the people in her neighborhood pull together whatever ingredients they can source to be distributed Food Not Bombs style. This community’s primary concern is that everyone is taken care of and that nobody is starving. Due to COVID, the distribution of the oxygen supply has been weaponized against the people. Their access to hospitals are blocked by military presence and intimidation tactics are implemented to prevent doctors from participating in the resistance.

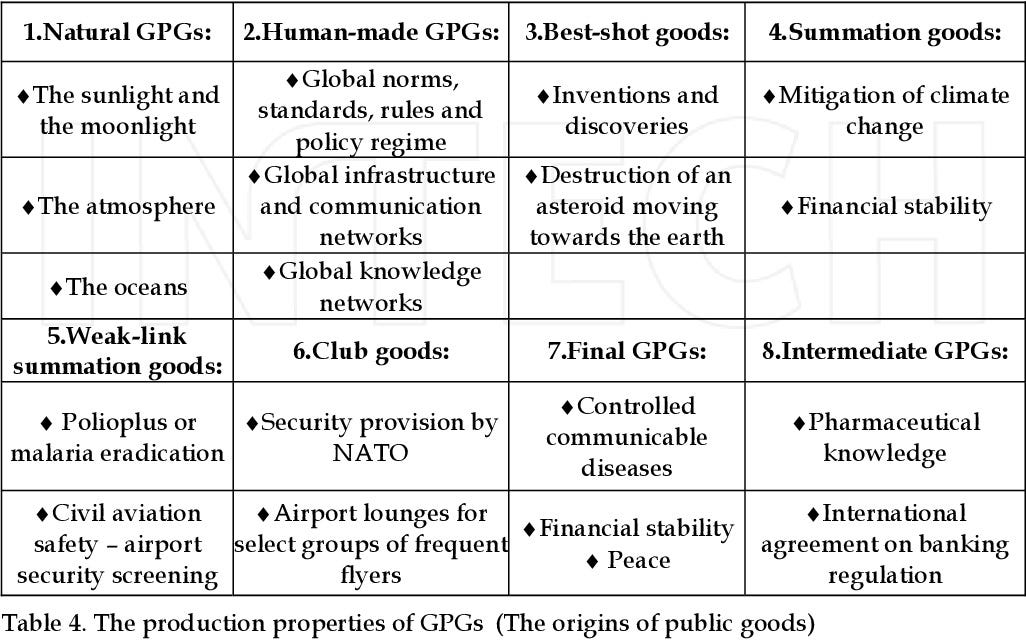

This is a powerful picture that you’re illustrating. Within the community that bestowed this grant for this project there is a lot of talk about public goods. Ethereum is purported to be a public good to the extent that it might facilitate a parallel, alternative, decentralized financial system, to create, generate and distribute value, to put the means of production back in the hands of the people. A public good might be differentiated from private goods and from common goods. They are largely defined by economic needs through ethical language, so that individuals should not be barred access, to ensure that they remain universally accessible as a foundational human right, maybe even a natural right.

Do any such things exist in our economy these days?

I live in New Mexico and around these parts it is quite common to discuss water with strangers. It’s more than empty platitudes about the weather, but a mater of life and death, or at least of livelihood. Will our reservoir fill up with enough water for the crops to grow this year, or will they need to be burned? There are tributaries that span from Canada to Mexico and the international water rights issue is a hot topic. The USA has been increasingly diverting the water supply to commercial and industrial purposes, contributing to increased sprawl and desertification. There is also a colonial weight to these issues, with acequias in some areas being dated to be over 300 years old, revealing a very old story of diverting water away from indigenous reservoirs towards European settlements. Another side of the issue might be approached from the perspective of the farmers that have been working this land for generations and who suddenly find their reliable water supplies diverted to suburban homes. Such a complex, multifaceted issue begs the question of how technology might support or protect water as a public good, or if it in fact contributes to its scarcity and facilitates a tragedy of the commons.

With the situation in Myanmar, how can the government be allowed to exist — by the global community — if the people are being denied the most basic access to food, clean water, and electricity?

If Ethereum might constitute a new meta economy, then it seems like one needs to have their basic needs already taken care of by some other means in order to participate. Can Ethereum — or any cryptocurrency for that matter — take care of our basic needs and protect the material public goods that sustain us? I struggle to understand how. My partner and I have been contemplating how NFTs and crypto might strengthen our fundraising here in the States, but I admit that we remain very skeptical about the whole situation. We’re also very curious. How might what’s happening in Myanmar inform our use of cryptocurrency in relation to this new economy that’s starting to emerge? Also, where’s the reciprocity? How does a virtual economy purporting to exist outside or parallel to the current economic infrastructure reciprocate with the local needs of the community we have been discussing?

Perhaps we might explore this issue in our ongoing conversation and seek to discover or define an opportunity for crypto to facilitate the distribution of resources to these people that are being barred access. We might make it our mission to try to figure out — from our limited technical understanding — how to increase the resolution on this problem space to build bridges with socially conscious web3 engineers and use crypto to coordinate and orchestrate collaboration between these worlds. How can the meta economy of crypto help people in need obtain the physical materials they require for survival, especially considering their limited access to open and free media outlets? We need to enlist an expert to steer us on this course. Any volunteers?

This series is made possible by a generous grant awarded by MolochDAO. Thank you Moloch!