JULIAN DUPONT IN CONVERSATION WITH TRAVIS WYCHE

Perhaps you want to talk about the content of your thesis. You said you’re in the last 1000 words of the document and that you’re in the process of connecting a few difficult points. I would also love to hear you provide an overview of your orchestration of the indigenous University and to talk a bit about your process with your performances and your exhibitions, to your artistic practice, and how they create a bridge between the modern art world and the local indigenous communities. We might emphasize the coordination of these groups of people and the curation of exhibitions as a coordination effort between many different kinds of people. I remember that one of your exhibitions concerns the coca plant, which has a notorious reputation as a controlled narcotic substance while also being a sacred plant for indigenous people. Maybe this would tie in to a conversation about resource flows and resource management.

I think both directions can meet at some point and this will be a good way to start the conversation, with the articulation and coordination of the relationship with the Nasa Indigenous Communities that we’ve been working with. Let’s start straight away with that matrix.

I’ll follow your lead.

Perfect. It’s very important to highlight that the possibility to work with the Nasa indigenous communities — which has opened a constellation of work with the Yanakuna, with the Kokonuko, with the Misak communities, and with the Nasa communities in the region of Cauca in the southwestern area of Colombia — that the possibility was opened through a relationship based on trust and friendship. That’s a very important point. This provided the solid ground to coordinate the very difficult and complex constant translations that became the core project. The initial conversation was with Luis Yunda, a member of the Nasa indigenous community who has become one of my best friends. I’m in France and he’s in the rural areas of Colombia, but we talk every two or three days. That’s something very important to highlight for me.

The initial conversation that I had with Luis was through a ceremony of harmonization; the traditional doctors of the Nasa community call it a ritual for cleansing the body. This was in 2010 and at that moment I had been experiencing health complications. My body and my feeling of being in the world was in a very chaotic state. My partner at the time was working on a thesis on the relationship between her Western citizenship and her roots in indigenous cosmogony. She connected me with Luis and we went to the mountains, to one of the spaces that the Indigenous university had at the time, and that night I experienced a very resonant system of perception of the world that I had been contemplating through my installation practice and sculpture and from my classes on contemporary art practice at the universities. It was the first time that I felt that this constellation of rethinking our relationship with space and our relationship with objects was understood by someone that had a completely different code and references for understanding space. He was talking to me like one of my professors of installation art; he was making connections that resonated with very complex spatial theories, like Rosalind Krauss with her text The Sculpture in the Expanded Field. At the time I was obsessed with that text.

Ohhh, me too! The notion of the expanded field really expanded my mind. That essay was very influential for me as well.

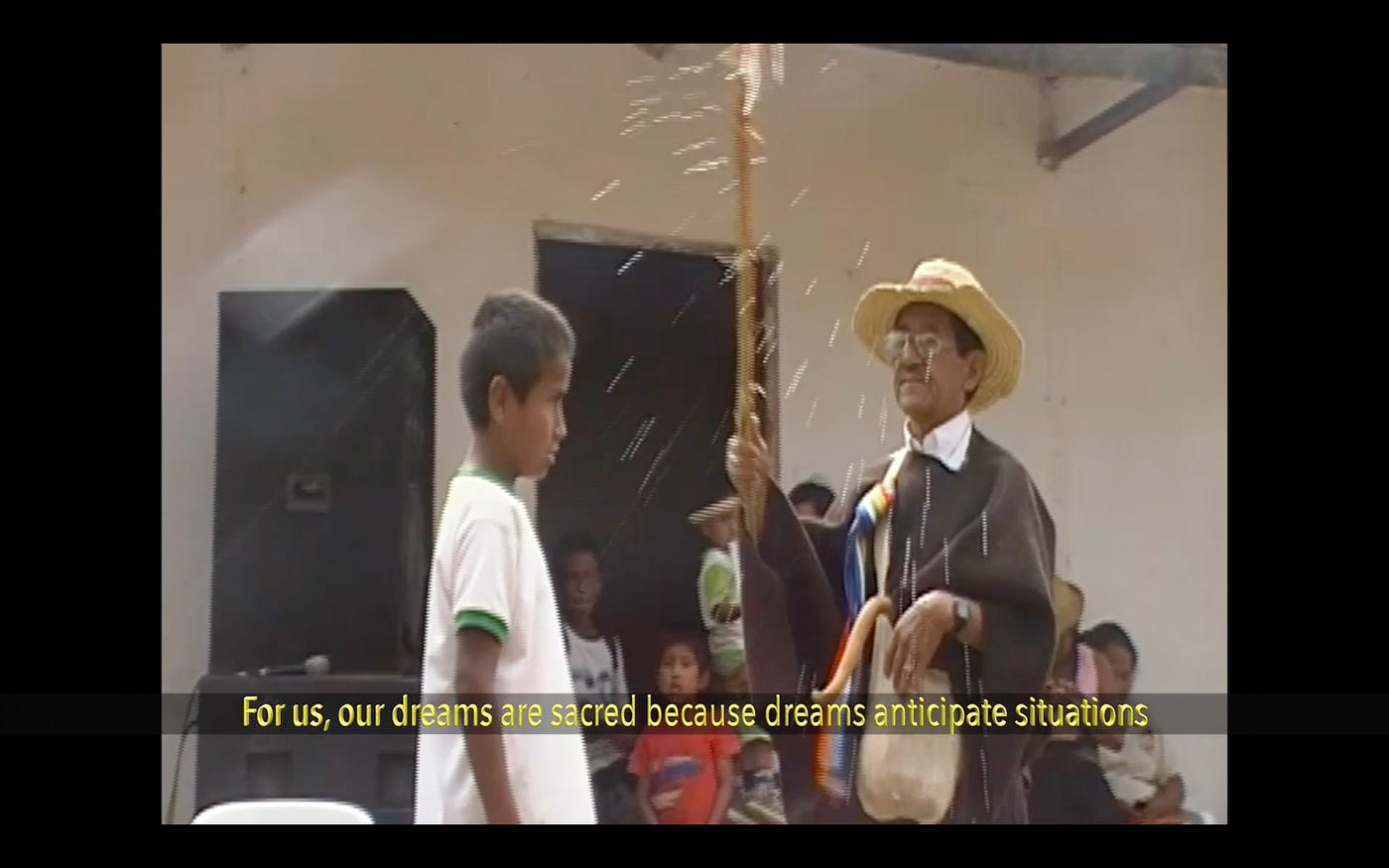

At the time, I was completely fascinated by the overlapping layers between architecture and sculpture — space and non-space — and how that could create a new paradigm of relations towards space and our articulation of spatial formations. It was very impressive to have a similar resonance with Luis. When we arrived at the mountain, the first thing he did was put a stick on the ground that he had bathed in the sacred lake of the community. That was the first point of entry to what the night would be opening for us. Without that connection, the energies and the channeling of the codes that he would be reading would not work. This happened at five or six in the afternoon and after I started to see how everything that arrived into that space was like a code he was reading. If the cloud arrived from left to right, if the sound of the animals present that night came from right to left, these directional flows were significant. There’s something key to understand in this inverse dialectical system of tracing connections, from the body to the Earth, as signals on the body.

This sounds to me a bit like a process of divination, evoking an oracle and feeding information into it in order to decipher messages from other beings or dimensions; a process of transcendental encryption. Common examples are tea leaves dropped in water or the hexagrams of the I Ching, a system composed of symbols derived from cracks in a tortoise shell to be deciphered by an expert seer to extend a bridge between the information of the transcendental realm and the material realm. Is that a relevant or interesting comparison to make?

The I Ching is a resonant comparison. Taking into consideration the embedded relational landscape of mineral and ecological conversations, there is something particular to the indigenous epistemology occurring here. I find it particularly important in the political configuration of the current situation on climate change and the configuration of biopolitics and sovereignty these days. Let me tell you more about my experiences that night.

We started to chew the coca plants. This is the sacred plant for the Nasa communities and — as you were saying — this opens a very powerful conversation that puts into question the neoliberal practices of global capitalism related to the production of cocaine and how this opens — in the same territories that these things are happening — these other relational frames towards the coca plant. In the ritual with Luis, chewing coca was a very exhausting exercise because we started at five in the afternoon and continued until 6 am in the morning. We were chewing and chewing as an exercise of cleansing our bodies throughout the night. By 1am, we were completely exhausted.

In the middle of the night, I remember I was chewing the coca leaves and I didn’t understand completely that we were not supposed to swallow the saliva with the coca. Luis gave me those instructions at the beginning, but I didn’t completely understand them. For the first five hours I was swallowing my saliva and at some point I remember the arrival of an immense white cloud. It arrived like a presence in front of us and then everything became a white cloud. Luis was very worried. He was telling me: You are carrying something that is very, very, very heavy. I don’t know what it is. When he realized I was swallowing the saliva, he told me he would give me a few plants in a liquid and I would immediately vomit and within one minute the white cloud would disappear. That was the first uncanny experience of the night. I vomited and after a minute the cloud completely disappeared. Such a moment made me question my whole system of beliefs. It was very important. The first thing that popped into my mind was that this was such an easy trick that he was playing on my mind in order to make me believe. These condescending affirmations come from our Western rationality and the moment of disbelief is an important break.

It’s an epistemic break, a break with reality that generates the momentum of an ontological pivot. Without the impetus of the plants, the ceremony, and the guidance, perhaps we wouldn’t be able to learn to see the world differently. Or maybe it could be described as an essential process of unlearning the way that we see that facilitates a new way of seeing.

That’s really accurate. I was amazed by the fact that Luis was presenting me with what I had been studying as movements of deconstruction, of poststructuralism in a theoretical landscape, and I was experiencing this as a form of life, as something really powerful.

The most shocking moment was at the end of the ceremony. The whole night Luis was catching fireflies with an impeccable technique. He was seeing fireflies 10 meters away and jumping to catch them, collecting them into a bag. At the end of the night he buried them in a hole in the Earth. When we were about to finish the ceremony, he called to me and told me that I would take the stick and hit the ground as hard as I could. If a lightning bolt didn’t appear on the horizon at the moment of hitting the ground we would need to stay in the ritual, meaning that the work had not been closed in the proper way. I was very skeptical, but I took the stick and hit the ground with all my force and there was strong lightning in the sky. Rationality returned to make me wonder: *what the fuck is happening here? *That was the closing point of the ritual ceremony.

I came back to my city life and I knew something had moved in me. I was in a totally different state of emotions. As you were saying, an epistemic break happened that revealed to me a different take on things. This is how I started my friendship with Luis and I used to go and meet him every six months. He invited me to community ritual ceremonies and I started to perceive a whole constellation of relationships. Since I was a kid I had always been traveling with my family, from one city to the other, but I was never aware of the rural experience in between. I had no access to the rural territories beyond the images presented on TV, describing in disrespectful and colonial terms how the indigenous are part of an archaic time that has passed.

After six or seven years, Luis introduced me to his Master, his professor of ancestral Medicine, Don Misael. I started to share with them in a space of reunion, a Congress of traditional doctors that come from different parts of the territories. This initiated the awareness that led to the Autonomous Intercultural Indigenous University.

Powerful title.

Yes. This is the educational project of CRIC, the Indigenous Regional Council of Cauca. They envisioned a form of education in the context of Indigenous knowledge and is one of the most important social organizations existing in Colombia. It entails the movement of recuperation of lands by Indigenous communities that started in the context of terrraje. The colonial landscape was configured in such a way that a few families in this particular territory of Cauca owned most of the land. All the friends that I studied with in high school were all descendants from these aristocratic families that used to own 98% of the territorial configuration of this state. The Indigenous that used to live in those territories were allowed to stay in those lands by paying what is called el terraje. The landlord’s allowed the Indigenous to live there, but in order to work they needed to pay retribution.

It’s more than tax, more akin to rent, and it actually sounds like a feudalist contract, like they became indentured feudalist servants.

Absolutely. A figure of slavery, basically. That was the landscape of operation. In the 1950s, the community started to reunite to fight for the reconfiguration of recovering lands and to put down el terraje and the organization started to take shape. One of the early leaders named Manuel Quintín Lame has an incredible book called The Indigenous that Learned How to Think with the Forests. He is an emblematic figure in the fight for lands in the indigenous context of el Cauca. This very wise guy learned how to read and write Spanish and studied the legal frame of Colombian jurisdiction to go to court and defend himself, which was unprecedented at the time. He gained an incredible reputation as he started to win legal cases, defending himself, but every time he would win a case he would end up in prison for the next three years. The Aristocracy didn’t know what to do with him and he spent most of his life in prison. He later started a revolutionary movement for recovering lands for Indigenous communities, serving as the inspiration for CRIC, the Indigenous Regional Council of Cauca.

In that context, the Autonomous Intercultural Indigenous University continues to develop an educational program that offers career programs like Revitalization of Mother Earth. This is an incredible educational project that is structured in the context of the recovery of lands and social struggle that existed for 20 years without being recognized by the educational system of the government of Colombia. As part of the struggle and the conversations that they conducted with the Colombian government, they have recently been approved by the Ministry of Education as an accepted University of the educational system in Colombia. This context opened up the potential for me to contribute to the conversation and process.

I was interested in articulating a project tracing the Nazca lines in Peru, these big constructions of astronomical proportions that marked the space like expanded drawings, referencing Robert Smithson, Andy Goldsworthy, and what is commonly referred to as* Land Art*. Through the friendships that I already had in the communities, I presented the project to the authorities of the university. They listened to me without embracing the articulation of the project, but after three years they found resonance with what I was proposing. Those conversations led to the first exhibition where I made a proposal to the communities to participate in an exercise of performative resistance in the context of the colonial landscape of Popayán, the city where I was born. I received an invitation to do an exhibition in a space that is called The Guillermo Valencia theater. Guillermo Valencia was part of one of these powerful families that were the owners of the whole territory a few centuries ago, but that today are considered the figures that have constructed the Colombian identity by referencing the social aspiration to grow. The distorted figures of progress are embedded in those colonial articulations of identity. The exhibition was scheduled during the Catholic holy week, so with all the Catholic morals and political structures of good customs embedded in the context we proposed an exhibition around the coca plant serving as the ritual matrix of the space.

I had previously been working on an installation where I used to put coca leaves inside of painted bags to address the biassed hypervisibility embedded in our Western manner of addressing the coca narrative. It was a way to show a package of our publicity-dialectical system to relate to the coca plant, but also, in a more metaphysical way, inside that distorted vision were coca leaves harmonized by the traditional doctors of the communities. Accompanying the coca plants was an indigenous guard, a version of an army without guns. It’s an army that just has the body and the communitary force as a way to defend and to also recover territory. In a conflictual zone like Colombia, it’s a very powerful symbol of resistance. The CRIC organization participated in this space for contemporary art and it was a very moving experience for everyone. I remember that at the end of the exhibition we were all in tears. It allowed me to feel corporeally discriminated against by the entire colonial landscape in the very place where I was born. It was very interesting for my family as well, because the work addressed the social landscape instilled by our education and openly put it into question. It was a moment full of intense emotions that allowed a bond with the communities to form, for them to feel that we were in trust, and that we were providing a common place to question. Trust was so essential for community foundations, as a guiding force for the design of the projects and organizations of the community, and in the founding of the university.

I had a few associations that I wanted to ask you about. With your performative sculpture practice you mentioned an indebtedness to earthwork artists, Robert Smithson and his contemporaries. I would also evoke the social sculpture that was happening a little bit earlier by Joseph Beuys and Marcel Broodthaers and James Lee Byars, an American conceptual artist. On one hand there’s the notion of social sculpture as a conceptual-aesthetic practice leveraged towards effacing political and social change, specifically within the radicalized youth movement of that time. The other aspect we might consider is their wonderful language of materials, their ability to wield iconographic objects and specific compositions to evoke transcendental or metaphysical or even spiritual resonances.

Joseph Beuys had his cane and felt and fat and there’s the well known performance where he attempts to communicate with a coyote. This is commonly referred to as an endurance piece where he put his own physical well being on the line, but I feel that reading grotesquely dampens the nuance of expanded material sensitivities and interspecies communication that he was attempting. Marcel Broodsthaers used his mussel shells and eggs as archetypes again and again in his works to evoke cosmological symbolism; the secret yoke held within, the juicy muscle morsel, the flesh that has calcified itself into a mineral-mollusk as an impossible attempt to seal itself from the world. James Lee Byars is known for his use of gold foil, among many other things. This is a really delicious example, because there is a cynicism built into it, a nihilism maybe, that the gold foil is used to create a skin over banal forms, rendering it seemingly precious while building affinities with golden Buddhas and other spiritual iconography, architecture, and sculpture. Yet his usage is also a superficial usage, evoking banal or mundane environments. James Lee Buyers is most well known for wearing a hat, an icon that he borrows from Joseph Beuys, and his whole persona is a kind of mimicry of the shammanic father figure of Beuys as the original social sculptor.

I’m wondering if you feel any kind of affinity to these kinds of artistic organization. Within the artistic persona there’s a bridge extending between performance art and social organizing through the material usage and the rendering of the profane world into sacred objects. I’m thinking about the coca and Luis’ stick, the stick that strikes the earth, and your use of a chainsaw to draw the trajectories of satellites across the Earth that are both ubiquitous and invisible simultaneously. Maybe this is reaching too far, but I also want to try to form a linkage to cryptocurrency. It’s a thing and a non-thing. It’s real, because we can render it into material goods and services, but it’s also completely virtual, arguably even more virtual than money already was and is, which is to say pretty spectacularly virtual. On the American dollar bill it is clearly rendered in God we trust and there is a tradition of faith in the common good that the currency represents as a symbol to the people that back it, or so the story goes. We participate in the economy and we exchange these notes as a symbolic representation of our collective faith in the system that we’re participating in. It might be argued that cryptocurrency is atheistic, or at least agnostic. Maybe crypto attempts a multiculturalism that actually becomes just more of the same globalization, striving to be radically inclusive without a spiritual grounding in the earth to contextualize our ability to believe in it as a system. There’s a paradoxical skepticism around trust in the crypto community and I wonder if there’s some way of correlating that skepticism back to becoming dislodged from the terraforma. Sorry that’s a bit of a stretch…

No, let’s go there! Maybe it will lead to an exciting epistemic break. It’s an interesting constellation of connections between the work of Beuys, Broodthaers, and Byers. We could include them in the difficulties I have experienced in the configuration of the conversation with the Nasa communities through the dialectical imperatives we have constructed in our Western resolution of the symbolic. In the Nasa communities, there’s no word Art. That’s a performative resolution of materiality that has not been resolved and puts into question the way that the liberal fields of our Western societies have created an image of freedom towards that symbolic imperative of Art. The roots of liberal conversations in Western societies are built upon a colonial foundation, it’s important to remember. That being said, how do we resolve what we have resolved through art, without art? How do we resolve what we have resolved through the symbolic, without the symbolic? What is the material conversation that the Nasa traditional doctors experience through their relations with plants that we have constructed as art? How could they work in a different way? In what way could we perform the potential of what is opened through these conceptions that will not become the exotic landscape of cannibal necessities?

In Paris last year, there was a humongous emergence of indigenous exhibitions. I went to these spaces and did not feel any critical inversion; there was no reversal of the mirror, but instead the ongoing validation of a Western entropy as otherness.

Sorry, could you clarify that? There was a falsity that you were keenly aware of, as though the indigenous works were being appropriated and fetishized and this constituted a failure? There was a missed opportunity?

Yes, let me clarify. The identitarian card played by multicultural configurations of neoliberal policies have a lot to do with bringing you these manufactured exhibitions presenting (supposed) Indigenous epistemology without structurally performing the ontological turn, without the voice of the community being embedded in that presentation. There are experiences where you find yourself in the prevalence of the institution, within the embedded logic of power of object dialectics that will not allow a conversation between selves as forest-thinking, to allow for a mode of becoming beyond just a metaphorical narrative. I could try to connect this with what you were tracing with cryptocurrency.

The question of how we could resolve what we have come to consider as art emancipated from the resolution of art is a notion that is also applicable to the terms of labor. How do we resolve the problem of labor not procuring emancipation through labor? How do we think ourselves through our relations towards each other and towards the Earth beyond mere systems of production, beyond the terms of productive labor? My conversations with the shamans and with traditional doctors serves as proof. Although we can conceive of their actions as work or nested within a system of labor, it cannot be reduced to that labor and is also something other. It cannot be contained by the concept of labor. It’s an other than himself space. There’s another relational landscape entangled on top of labor and a consideration of labor beyond the legible deployment of the social system. We could play with these ideas in relation to cryptocurrency. How might we re-think those economic systems and configurations untethered from virtuality?

There’s an important point to be made here regarding the role of the artist in society. The latent potential of Western art is to create distance from the phenomenal world so that we might engage with this potential and pivot our perspective, but how do we perform this without the delusional infrastructure of what art has become? How do we internalize the lessons of art and integrate them into our everyday life, so that art itself might dissolve? This is especially pertinent in the Eurocentric or colonial notion of art, concretized and preserved by the museum that consumes the indigenous artifacts of the world, ripping apart communities in the name of anthropology and dissociating ourselves further from the earth under the banner of ecology.

There’s a European tradition within the arts attempting to reconfigure our relationship to labor and value, from radical avant garde movements like Dada or Lettrism. Situationism was closely tied to the May 68 worker-student uprisings which instigated a global revision of industrial factory conditions and brought about reformation in work schedules and worker compensation. Two more recent examples might be Liam Gillick, who organizes expanded sculptural installation exhibitions that experiment with every facet of the labor that funnels into the construction of precarious scenarios. The lasting effect of his work is an ad hoc, fragmented architectural strategy that serves as a deconstructed stage for considering the labor itself, following in the artistic tradition of stripping away all of the extraneous content to conduct a meditation on labor.

There’s the well-known text by Sternberg press called Are You Working Too Much? Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor and Art that has circulated through my artist-friend circles. And then Franco Bifo Berardi wrote an incredible book called The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy, where he attempts to — admittedly from a Eurocentric point of view — identify the social and industrial operations of metaphysics and transcendentalism, or spirituality, within a Marxist theory of labor.

I default back to the necessity of positioning oneself to receive the agnostic sacrament in order to unlearn the ways that we have known, acknowledging the paradox of attempting to identify and solve for the problem of this worlding vision while remaining firmly embedded within this decaying vision of a world. Doing so will only perpetuate more of the same reality distortion tunnel, which leads to an inevitable appropriation of the identity of the other, and the violence of othering more generally. Perhaps we can be generous to say that this has always been the Western artistic tradition; not so much that it has failed, but that it has, in fact, succeeded in its monstrous efficiency by appropriating itself back into the very system that it has attempted to critique. Reason enough to let it go? At what point might we concede that our goal has changed and that it’s no longer a matter of accumulating more artifacts in the museum, more concepts for our colonizing epistemology, but to intentionally dismantle our perspective? We must realize that the only sustainable future economy is one that is actively working to deconstruct the centralized legacy systems that continue to terrorize and territorialize the landscape, rendering it legible to the machinic vision that has reduced human agents — all agents, really — into units, bound them into metrics, compartmentalized them within a tyrannical numerical framework, incessantly insisting upon mathematical vision, of the supremacy of the quantifying eye of the surveyor. If there’s something that we might learn from art and if there’s some kind of correlation that we might draw to a rootedness within indigenous ways of knowing, perhaps it’s the need to unlearn the toxic colonial vision that has come to in-form and out-form our entire worldview, to learn how to begin dreaming differently. It’s an imagination problem; it always has been.

This series is made possible by a generous grant awarded by MolochDAO. Thank you Moloch!